High on the Cassin Ridge a few days after summiting Denali via the West Buttress

Wade tapped me on the shoulder. “I’m not up for this,” he said. My heart sank. I knew it was the right call: he’d been under the weather for a few days. But we had trained so hard for Denali’s Cassin Ridge, and now, moments before dropping into the abyss, it seemed we were on the verge of tapping out.

By then I was nearing the end of my first climbing trip to Alaska. My plan going in was an obvious choice for a Colorado cowboy looking for a wide-eyed wake-up call: acclimatize with a hot lap of the West Buttress of Denali, then go blast the Cassin Ridge. Maybe it was too ambitious, but I didn’t care. I had been dreaming of the Cassin for years.

I started working toward these goals in November 2016, when the stars aligned and I first realized I’d be able to make the trip a reality. I wanted to arrive in Talkeetna in the best possible shape, so I approached my training with the same seriousness as the endeavor. If our fitness was so high as to be a nonissue, my partners and I would be able to take full advantage of any weather windows.

We committed to training for the trip together. Our physical preparation consisted of a mix of time in the mountains; other outside training like skiing, hiking, and climbing; and gym strength and conditioning. To keep us on target, I put together a checklist of expedition standards for all of us to complete before we landed on the Kahiltna Glacier (see end of post; note that this was my creation, not something I got from Uphill Athlete). The only standards I didn’t hit were a second big day of dragging a sled and the total number of ice pitches.

I coach at the Alpine Training Center in Boulder, so I modified my strength programming with a little help from the ATC’s owner, Connie Sciolino. We integrated Scott’s Killer Core Routine into my work.

A main component of our training regimen was Uphill Athlete’s 24-Week Expeditionary Mountaineering Training Program. The weighted pack carry was particularly beneficial: I followed the weight increment progression exactly, and I could see and track my improvement. My go-to for this was Mount Morrison, near my home in Golden, Colorado; there’s a trail that climbs about 2,000 feet in 1.7 miles. When I started the program in December, my daughter was just four months old and weighed about 13 pounds. I incorporated her body weight into my prescribed load so that I could get my work done and spend time with her. The only downside to this bonding-slash-training is that I would have to wash her sweat-soaked winter onesie after each workout.

Another hard-core training session with my daughter Avery (age 9 months in this photo)

Our simulator days were the last big piece of the training puzzle. We headed up alpine routes in Colorado with packs as heavy as 43 pounds, and we’d intentionally spend nights out and bivy in inopportune locations as high as possible to mimic what we might encounter on the Cassin Ridge. Long, cold days with weight were super beneficial for their specificity to the objective.

Training in Colorado for the Cassin Ridge. My pack weighed 43 pounds on this trip up the Blitzen Ridge.

In mid-May my partner Wade Morris and I boarded our red-eye to Anchorage (our third teammate had to drop out due to a foot injury). We were already anxious about having enough time on Denali, so midflight we started scheming ways to buy back a few days. The current schedule had us taking four days to get from Denver to Kahiltna. We cut that down to 24 hours: by the end of that first whirlwind day, which involved flights, shopping, a ranger briefing, and packing, we’d skied the 5.5 miles to the base of Ski Hill at 7,500 feet. It set the tone for the rest of the trip.

During the next few days, as we single-carried to 11,200-foot Camp and ferried our load to 14,000-foot Camp, we endured some grim weather. We encountered several large parties heading back to the airstrip cold, tired, and beaten down after days upon days in 14,000-foot Camp.

On our fourth day, we joined forces with two other climbers who had the exact same plan as us. Ryan Edwards was a friend of mine from Colorado, and I had messaged with Nate Kenney via Facebook for a few months leading up to the trip. We spent that day and the next climbing higher and continuing to acclimatize. With the exceptions of a couple of other groups, we were the only ones moving on the mountain. It was cold and windy—for us, the usual alpine fare. But those other parties we saw were later rescued and airlifted off Denali, on the verge of death from exposure.

Just when we thought we might get our first prime weather window, it snowed for three days, confining us to our cook tent. Then day 11 dawned clearer; by 10 a.m. there was enough visibility for us to see nearly the entire West Buttress. But no one had been up past the fixed lines in four days, and Ryan, Nate, Wade, and I weren’t stoked on breaking trail. It didn’t seem smart to kick off our attempt with that kind of effort.

Wade Morris (right) and I enjoying a typical whiteout day at 14,000-foot Camp

We sat in camp and watched a large Japanese team work their way up to the lines. A few hours later, we hefted our summit packs and started up after them.

At the Football Field at 19,000 feet, we paused for a check-in—fingers, toes, cheeks, stoke. It was cold and windy, but visibility was still good. We all “Michelin Manned up,” headed uphill for ten more minutes, then debriefed again. We repeated this pattern until we reached the summit, which we had all to ourselves.

That was May 30, and by June 3, we were getting antsy again, eager to launch for our real objective: the Cassin Ridge on the south face of Denali. I had budgeted only 25 days for the trip, and I was running out of time.

On the morning of June 5—after a few days spent monitoring the weather, weighing risk and reward, debating go or no-go—Wade and I woke to Nate rapping on our tent walls. He said it was splitter. The weather models told us we had 60 hours of variable conditions, then a huge storm would hit. It would have to be a 60-hour push or less. The four of us headed up to the West Rib Cut-Off at 2 p.m. that afternoon. The plan was to navigate the Seattle ’72 Ramp as a roped team of four, then we’d split into two teams of two on the route.

At the Cut-Off, Wade made the wise call to turn back. Fortunately for me, it didn’t mark the end of my attempt: Nate and Ryan invited me to continue up the Cassin with them. This was the first talk of a trio, and I was euphoric when they extended the offer. At the same time, I was upset to see one of my best friends walk back to camp alone. But I couldn’t dwell on it. It was now or never, and I continued toward the Seattle ’72 Ramp with Nate and Ryan.

We deemed the ramp too dangerous and opted instead to down-climb the West Rib, cross the Valley of Death, and ascend the Japanese Couloir. We moved efficiently through the hazard-riddled terrain of the Valley of Death and reached the bergschrund just below the Cassin Ridge. Smiling, we brewed up, poised to begin one of the most classic alpine climbs in the world.

With Nate running point, we simul-climbed delicately through the entire Japanese Couloir to Cassin Ledge. After a quick transition, I took the next block, leading us over the memorable Cowboy Arete to the first rock band. Ryan then took over, climbing smoothly through quickly deteriorating weather.

Unable to see more than ten feet ahead in the whiteout conditions, we pitched our two-man tent below the second rock band and bivied for about six hours. We weren’t planning on staying for so long, but between napping and melting snow for the next few sections of ridge, I heard from a friend back home (via my satellite messenger) that we’d have a window of high pressure for the rest of the day. We unzipped the tent, and the sun was shining through; no longer feeling so rushed, we spent a few hours eating and brewing more water before pushing on.

As we started the next block of climbing, we heard a huge crack! A massive serac calved off and annihilated our visible tracks crossing the Valley of Death, enveloping everything in a white cloud. Now super alert, we climbed fluidly. We negotiated the difficult second rock band—the hardest part of the route for us—and passed Big Bertha. Once into the nontechnical terrain, we unroped, moving silently and in sync on the upper stretches of the mountain.

At 18,000 feet, the temperature dropped and visibility worsened again. We threw on our insulating layers and continued up, one step at a time, ascending a system of gullies and rocky outcroppings for another 2,000 feet to the familiar Kahiltna Horn. Elated, we hugged as a trio then turned east toward the true summit.

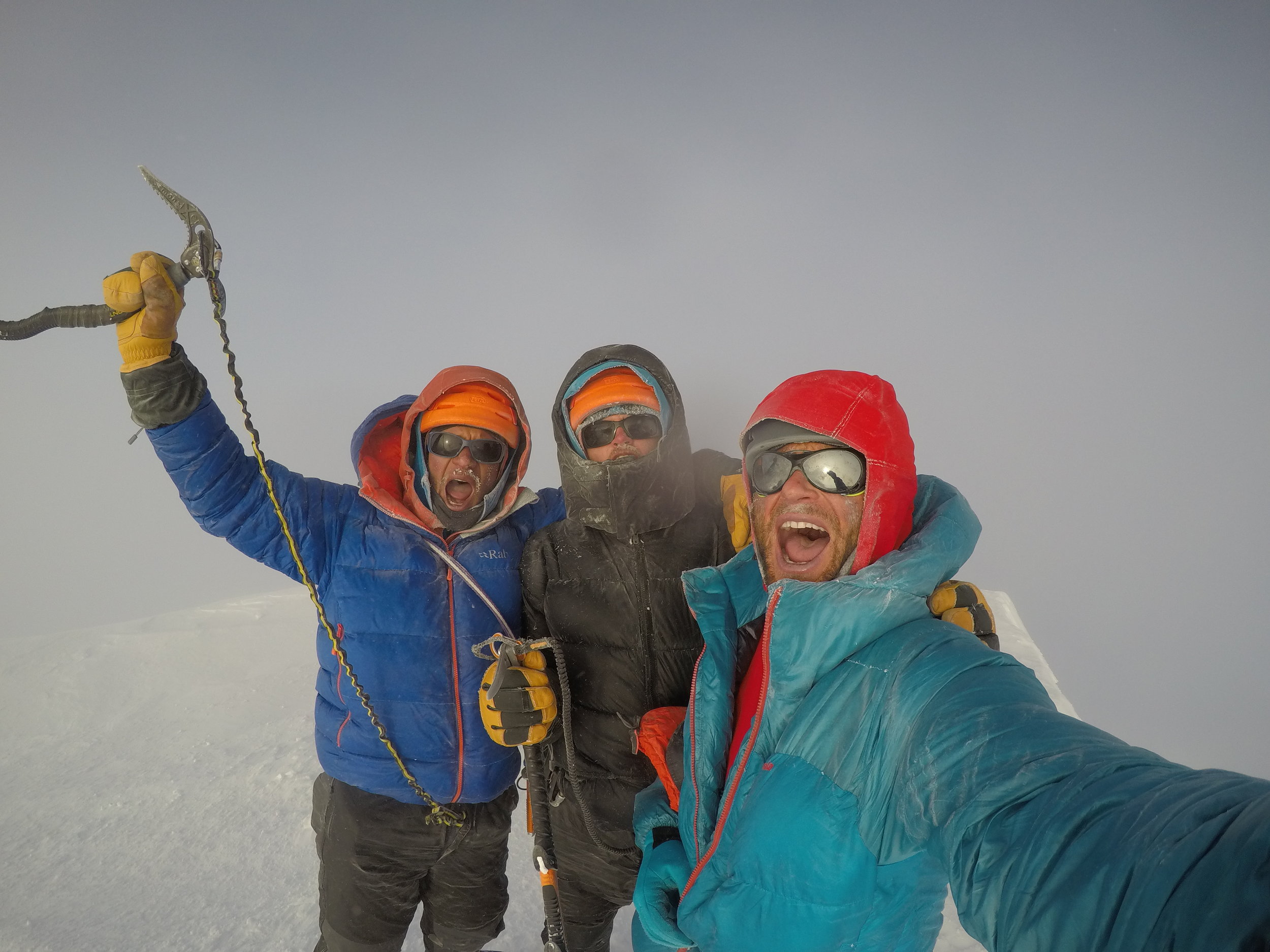

On June 6, 2017, we once again had the summit of the Denali completely to ourselves.

Ryan Edwards, Nate Kenney, and I on the summit of Denali for the second time on June 6, 2017, after climbing the Cassin Ridge

It was the middle of the night when we arrived back at 14,000-foot Camp. Wade had inflated my pad for me and had brewed up some water in a thermos. He knew I would be pretty beat. Those small gestures were a huge sign of his character; despite being bummed to have missed out on a second summit, he was still looking out for me. The next morning we packed up camp and skied down to the KIA for our trip home.

Throughout the expedition I could feel the months of dedicated training paying off. I felt it while dragging 150 pounds of gear around the lower mountains, and I felt it during the final 500 feet to our second Denali summit. We had simulated the Denali experience incredibly well in our Colorado backyard, and nothing seemed to catch us off-guard.

“The High One” threw some harsh conditions at us, as evidenced by the many helicopter transports removing sick and injured climbers from the mountain. It’s hard not to question your mountain sense during a maiden voyage to Alaska like this, but I can’t help but chalk our success up to fitness, amazing energy and enthusiasm from all members of the climbing team, good (enough) weather, and a whole lot of luck from the Alaskan mountain gods. I set lofty goals for a first visit to Alaska, and I achieved them. It didn’t feel like an accident.

On the Cassin Ridge, just as we received a break in the weather

***I originally wrote this article for Uphill Athlete with the help of Steve House. In my original article, I included some of the skills and endurance training benchmarks I set for myself. If you want to check them out, go visit the Uphill Athlete site for all the info.